When I tell people that I volunteer teach at a maximum-security prison, many people nod and tell me “that’s cool,” and some compliment me for being “generous.” But few understand what a deeply gratifying, enriching, and inspiring experience it is.

I wasn’t a newcomer to the prison environment. I’d been familiar with several prison visiting rooms over the course of the 17-year wrongful incarceration of my childhood friend, Marty Tankleff (who was eventually exonerated in 2007), and we had discussed prison life at length over the years. For several years I have also been teaching a course at Georgetown called “Prisons and Punishment,” which included visits to Jessup Correctional Institution and the D.C. Jail. And I had the surreal experience of playing tennis with the “inside team” at San Quentin State Prison in California, which I wrote about in Sports Illustrated. But these were always short visits in a controlled setting.

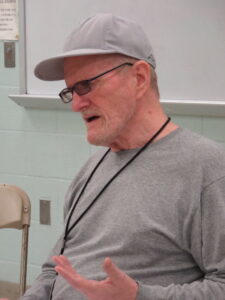

I started teaching at Jessup in the Fall 2014 semester because I wanted to have more sustained, open, and genuine interaction with inmates. I also wanted to provide an educational opportunity to a group of people who have largely been forgotten by society. Research has clearly shown that inmates who further their education while incarcerated will improve their behavior within the prison environment and will be less likely to pursue a life of crime after their eventually release. The Jessup Scholars Program provided an ideal opportunity to create a productive educational environment in a classroom setting with minimal staff supervision, with a group of students who chose my class and were eager to learn.

The class was the same as one I have taught at Georgetown for many years, called “Fascism and Extremist Movements,” which I was also teaching in Fall 2014. In this course, we spend the first half of the semester examining historical fascism, and in the second half we focus on different contemporary extremist movements. After some deliberation, the prison administrators decided that a course entitled “Fascism” might send the wrong message in a prison setting (after all, gangs and other extremist groups might think it is a “how to” course), so they suggested that I change the title to “World History,” which I came to embrace.

As the weeks went by, I was teaching the same material in both places—on Mondays at Georgetown with 16 students, on Tuesdays at Jessup with 35 students. Although obviously the level of academic preparation was different across the two groups, I was continuously impressed by the high-quality discussions maintained by the majority of my Jessup students.

We had a particularly enlightening conversation about the concept of charisma, in which we contrasted Max Weber’s rather strict definition that refers to the “exceptional sanctity, heroism or exemplary character of an individual person” as distinct from the common usage in political and popular discourse that essentially refers to “popularity.” We then discussed the role of charisma in the appeal and power of historical figures such as Hitler and Stalin (whose charisma was not personal, but rather deflected into the impersonal institution of the Communist Party), as well as more “positive” leaders such as Nelson Mandela and Martin Luther King, Jr. And we debated whether modern-day politicians like Bill Clinton or Barack Obama meet the Weberian criteria for charisma. Throughout this memorable and engaging discussion, I was astounded by the Jessup students’ knowledge of “world history” and their desire to apply it creatively to the new conception language and framework I had given them.

The students also kept me on my toes by occasionally offering “outside the box” comments that were often insightful, even if sometimes evocative and provocative. For example, when we were contrasting Mussolini and Hitler’s degree of totalitarian control, one student explained the implications of Mussolini being softer on opponents in his midst by analogizing to his experience with the Baltimore underworld, claiming that Mussolini was “like a pimp who falls in love with one of his ho’s and then loses the respect of his followers.” And every once in a while there would be a random comment or question from someone who was quite lost—e.g., after a long discussion of the role of anti-Semitism in German culture, one student raised his hand and asked if German shepherds come from Germany. Overall, though, many of the Jessup students held their own, even by Georgetown standards.

As the weeks went by and my enthusiasm for teaching my “parallel classes” continued to grow, I decided to see if we could make them intersect for a week. So I approached the prison officials about the possibility of holding a joint class session at Jessup. To my delight, they were very accommodating and helpful, understanding the clear educational benefit. My Georgetown students—several of whom had previously taken my “Prisons” class that included a group tour of Jessup—were excited about the opportunity. And, needless to say, my Jessup students were thrilled (and one asked jokingly if we could hold the class at Georgetown instead of Jessup).

In preparing for the joint session, I worked hard to create a format and structure that would make it a productive, effective, and memorable class for all students. The topic we were covering that week was “Right-Wing Extremism in Contemporary Europe.” Given the nearly polar opposite racial imbalances of my two groups of students, this seemed more suitable than the topics of the following two weeks, White-Power and Black-Power extremism.

The main objective of the joint class session was to create a comfortable classroom dynamic whereby the students from both groups could interact in a way that was not only relaxed and respectful, but during which they could momentarily leave behind their vastly different backgrounds, situations, and opportunities, in order to discuss and debate the materials as “fellow students.” I wanted the experience to be more than a mere novelty for both sides. I especially wanted my Georgetown students to appreciate the humanity, intelligence, and determination that my Jessup students bring to my classroom every week. My hope was that it would move and change them, helping them to think differently about “criminals” and “felons” who are so stigmatized—and forgotten—in our society.

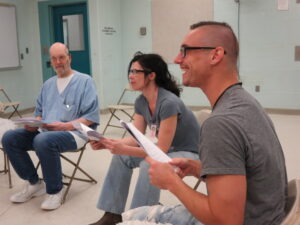

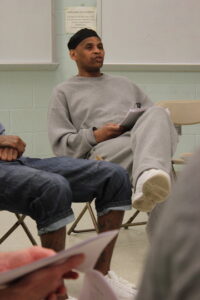

The class session was phenomenal. We arranged the chairs in a larger circle, mixed in the Georgetown and Jessup students, and had some light ice-breakers to launch the conversation. Then I divided them into eight smaller groups and had each group tackle a set of core questions about the topic (mainly evaluating how contemporary right-wing movements relate to historical fascism in several different respects). When we returned to the full group, each smaller group was responsible for leading the discussion on a particular question. The time flew by, and the conversation never stopped flowing. The Georgetown students became more comfortable and relaxed, and the Jessup students were able to contribute their insights. For just a short while, my two classes became one, and both sets of students were able to shine.

As someone who has been a professor for well over a decade now, this was without question my most thrilling moment as a teacher. Many of my Georgetown students described it as their most memorable educational experience, and my Jessup students were deeply appreciative to have had the opportunity to share a “Georgetown class.”

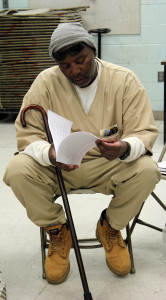

The next few sessions at Jessup went smoothly, and we closed out the semester with a wide-ranging discussion of the topic “Fascism in Our Future?” As the final class came to a close, it dawned on me that this remarkable experience was about to end—at least for the Fall 2014 semester—and that I was going to miss this class tremendously.

Before handing out the Jessup certificates of completion to the 35 students in my Fall 2014 “World History” course, I offered my students some final remarks. I told them:

I want to thank you for having inspired me, in three different ways:

1) with your intelligence

I have learned so much from our discussions, from your thoughts and reactions to the readings and debates, and your points of view about human nature, social history, and world affairs.

2) with your sense of humor

We dealt with serious and solemn themes and topics—oppression, genocide, racism—and you were respectful towards me and each other. But you also realized that we learn more when we enjoy ourselves, and your jokes and levity were refreshing. I don’t know if I’ve ever laughed so much in a classroom before, and I really appreciated that.

3) with your courage

I understand that your everyday life here is not easy, and in many ways it is grim and depressing. I know that many of you have made choices in life that you now regret, and that the laws of our society have put you here as a result. But I want you to know that I greatly respect and admire how you have acted with class and dignity, even though there are temptations and pressures that try to push you in other directions. I know it’s not easy, but you have shown me what courage is about.

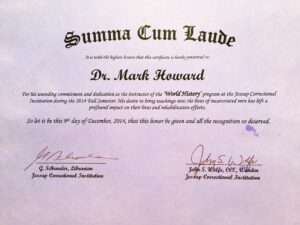

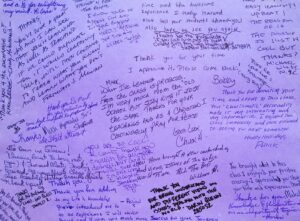

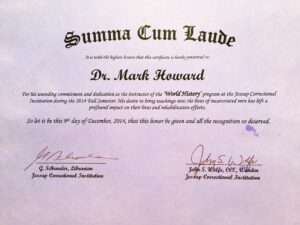

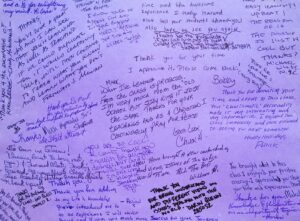

Not to be outdone, they provided me with a nicely-produced “Summa Cum Laude” certificate, and the back of the certificate was entirely filled with hand-written notes of thanks. When I arrived home later that evening, I sat down and read some of the most sincere, profound, and touching comments I’ve ever received. Here are just a few:

“You’ve done a great job, and I can see that you’re learning as well as teaching. If we could duplicate you, it would certainly help. Until then, continue to teach what you know and learn what you don’t.”

“You have brought a new understanding of issues about the entire world to me.”

“Thank you for adding to my life and knowledge. You’ve introduced me to an experience I will never forget, and I wish you much more success on your journey.”

It is now over one month later, and I can say that my journey will soon take me right back to Jessup for the Spring 2015 semester. I’m on sabbatical from Georgetown this semester, as I finish writing a book, but I’ll be in my Jessup classroom every week—teaching and learning.

Marc Howard

Professor of Government and Law

Georgetown University

mmh@georgetown.edu

Two months ago, the Attorney General Lorretta Lynch and the Secretary of Education Arne Duncan came to Jessup to announce a plan to offer Pell Grants to some prisoners again. They gave us until October 2nd to find a university partner to offer credit-bearing programs.

Two months ago, the Attorney General Lorretta Lynch and the Secretary of Education Arne Duncan came to Jessup to announce a plan to offer Pell Grants to some prisoners again. They gave us until October 2nd to find a university partner to offer credit-bearing programs.