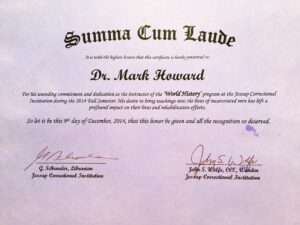

On April 30th 2014 students in Andrea Cantora’s Criminal Justice class presented their crime prevention program proposals. Here are the summaries of their proposed programs:

Sunshine Acers – An Alternative to Incarceration Program

“We have come up with an alternative to incarceration program that we truly believe could work in the future. We call it Sunshine Acres. Sunshine Acres is a place for first-time non-violent drug offenders to be opened up into a new world of entrepreneurship. As a group, we understand that drug dealers are making a lot of money because of the business they have been running. But the object of Sunshine Acres is to show them that it’s not the business that is wrong, it’s the product. The point would be to open their eyes to a new world. To show them what it would be like to live in a world where you don’t have to be in fear every time you find a new customer or make another transaction. The sole purpose of this project would be to point the drug dealers in a different direction away from selling drugs, and point them towards selling food, sports equipment, electronics, or something other than an illegal substance. This will then open doors to give them an option to live a better life.”

Evolving – A Prison Reentry Program

“The objective of the program Evolving is to provide a Community and Institution support system that would make available services that would address mental, emotional, spiritual, and financial needs of Incarcerated Citizen who has or who are serving long-term prison sentences. This organization was created and designed to help long term incarcerated men who have been counted out of life because of their long term prison sentences. We believe that there must be a support system established that would provide a sense of comfort, understanding, and hope for long term incarcerated men. During the pre-release stage incarcerated individuals will enter our Evolving program. During this stage we will be debriefing the inc arcerated individuals to get them out of the prison mindset. They will then be enrolled in special classes that consist of goal setting financial aid, and life planning. Also during the pre-release stage we will be contacting the inmate’s family members. We will be contacting the family members so that when it is time for them to come outside that they will have some type of support system other then the Evolving program. When released the individual will report to Evolving Quarters. They will spend one year here. This mansion-sized house is located on 15 acres or farmland with horses. Quarters include, in ground pool, full fitness center, basketball courts, bonus room, classrooms, computer lab, and a visiting center. On the first day of release our car service will pick you up and we will go to headquarters for a risk assessment. This assessment consists of more questions to help the “Evolves” plan for the “Evolvers” future.”

arcerated individuals to get them out of the prison mindset. They will then be enrolled in special classes that consist of goal setting financial aid, and life planning. Also during the pre-release stage we will be contacting the inmate’s family members. We will be contacting the family members so that when it is time for them to come outside that they will have some type of support system other then the Evolving program. When released the individual will report to Evolving Quarters. They will spend one year here. This mansion-sized house is located on 15 acres or farmland with horses. Quarters include, in ground pool, full fitness center, basketball courts, bonus room, classrooms, computer lab, and a visiting center. On the first day of release our car service will pick you up and we will go to headquarters for a risk assessment. This assessment consists of more questions to help the “Evolves” plan for the “Evolvers” future.”

The KOV Initiative (Knowledge, Opportunity, Vision) – An Alternative to Incarceration Program

“KOV Initiative is a boarding school setting designed for juveniles, ages 12 – 17 and adults ages 18 -34 both male and female to serve a maximum of 18 months. Its goal is to help participants reach their fullest potential by providing them with the proper knowledge, opportunity and vision needed to succeed in society. This program was created by the state to give first time, non-violent offenders a second chance at learning how to be a law abiding citizen with the proper learning tools to survive and make good decisions. With a budget of $10 million dollars, the state was able to renovate an old hotel building to house up to 500 inmates. This renovation is equipped with a kitchen, laundry room, conference rooms used for teaching and counseling sessions and an exercise room. We also offer religious teachings for inmates who want to have bible study. This school will operate near rural, farm-like settings, away from the city limits where crime tends to occur at a higher rate.”

Helping Youth of Today for Tomorrow – a Crime Prevention Program

“Our group’s program is focused crime prevention. We believe with our program we could start to see a decrease in crime. Many times crimes may occur due to conflict that people may have in the community. Conflict is something that people come in to contact with on a daily bases. We would also be warning them of the alternative to a law abiding life – prison. We believed that if we were to teach people other ways to deal with conflict then we would see a decrease in crime. Our program will be designed to give people the tools that they maybe be lacking to effectively communicate their conflict to others. The name of our program is called Helping Youth of Today for Tomorrow. We gave our program this name because we planned to focus on the youth which would give them tools that could be used now and in the future. We planned to focus on the younger generation, but make available workshops for the older generation as well.Some service that will be provided include different workshops like; Alternative to Violence program (AVP), anger management, communication skills, negotiation skills, mediation skills, social skills, life skills (etiquette, money management, and career focus).”