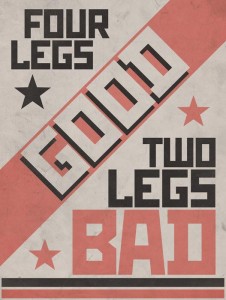

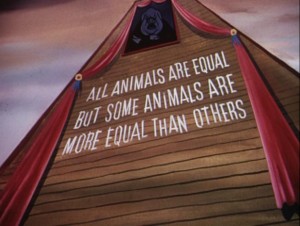

Animal Farm is starting to get depressing, but I think we all predicted that. And not all the animals are having a hard time. As top pig, Napoleon is in the pink. He’s even going to market and bringing home the bacon. By the end of these two chapters, Napoleon’s regime is definitely worse than that of Mr. Jones. As Napoleon’s  henchman, Squealer circulates disinformation, blaming everything bad that happens on the absent Snowball. He also accuses certain animals of plotting secretly with Snowball, which is obviously untrue. What makes matters worse is that the animals admit it, internalizing their self-hatred. Napoleon doesn’t even have the decency to give them a fair trial; he just has them taken round the back of the barn and the dog rip out their throats. So much for Commandment Six, “No Animal Shall Kill Any Other Animal.”

henchman, Squealer circulates disinformation, blaming everything bad that happens on the absent Snowball. He also accuses certain animals of plotting secretly with Snowball, which is obviously untrue. What makes matters worse is that the animals admit it, internalizing their self-hatred. Napoleon doesn’t even have the decency to give them a fair trial; he just has them taken round the back of the barn and the dog rip out their throats. So much for Commandment Six, “No Animal Shall Kill Any Other Animal.”

These two chapters are important because they show how the animals are being manipulated into following anything Squealer claims Napoleon has said. The animals are so obedient that they don’t even realize how gullible they are. The truth is, they’re so used to having someone else think for them, that they don’t even consider objecting. They just assume Napoleon is right all the time.

Although he uses the word “Comrade” and uses the inclusive “we,” Squealer is starting to speak in a formal way, beginning to isolate himself from his fellow beasts. No longer is he an everyday pig. Though he denies that the top pigs have power over the others, his speech, charisma and closeness to Napoleon all give Squealer implicit authority.

For example, when Squealer bans “Beasts of England,” he says, “In ‘Beasts of England,’ we expressed our longing for a better society in days to come. But that society has now been established. Clearly this song has no longer any purpose.” When he says “we,” he sounds as though he is speaking on behalf of the other animals, but he is also assuming that they all feel the same way. He is not open to disagreement or protest. He pretends to be a “pig of the people” but is actually authoritative and hard headed.

Although the book may be getting depressing, I’ve got a lot to look forward to. I really love hearing the men’s responses to this novel, because they’re so complex and interesting. I’m used to listening carefully to the thoughtful responses produced by Mr. Arey, for example, and Mr. Doyle, and Mr. Simpson, but last w eek I wasn’t prepared for Mr. Barnett’s paper. There was really too much for me to take in just by sitting listening to it—I had to take a copy home and read it again. And then there was Mr. Drummond’s impressively close reading. He gets right in there and turn the words themselves into a code to be cracked, creating mysteries he alone can solve. The progress of the pigs may be disheartening, but that of this group is just the opposite.

eek I wasn’t prepared for Mr. Barnett’s paper. There was really too much for me to take in just by sitting listening to it—I had to take a copy home and read it again. And then there was Mr. Drummond’s impressively close reading. He gets right in there and turn the words themselves into a code to be cracked, creating mysteries he alone can solve. The progress of the pigs may be disheartening, but that of this group is just the opposite.