Blog

-

Marshall Project Launched

A crucial resource launched today: The Marshall Project, “a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization covering America’s criminal justice system.” Check it out at www.themarshallproject.org.

-

Warren “Renaissanz Rzen” Hynson: Art Show at MICA

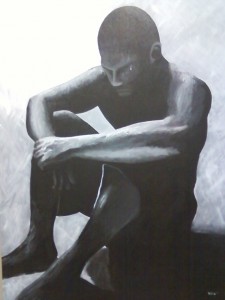

Warren Hynson, who works under the name Renaissanz Rzen, began painting after being inspired by the work of his fellow prison artists. His vibrant acrylic portraits of inmates help tell the story of his own struggle and the struggles of his comrades in exile. The exhibition took place in the Rosenberg Gallery, 2nd Floor of the Brown Center at the Maryland Institute College of Art, Wednesday, October 1-Tuesday, October 14. The reception on Friday, October 3 included a gallery talk by muralist, painter and outsider art authority Dr. Bob Hieronimus.

Click on the pictures to enlarge.

-

Renaissanz Rzen: Artist in Exile

Rosenberg Gallery, 2nd Floor of the Brown Center Maryland Institute College of Art Wednesday, October 1-Tuesday, October 14 Reception: Friday, October 3, 7 pm This show will feature the work of artist Warren Hynson, who works under the name Renaissanz Rzen. Hynson has spent more than 20 years in prison and is currently incarcerated in the Jessup Correctional Institution. He began painting after being inspired by the work of his fellow prison artists. His vibrant acrylic portraits of inmates help tell the story of his own struggle and the struggles of his comrades in exile.

This show will feature the work of artist Warren Hynson, who works under the name Renaissanz Rzen. Hynson has spent more than 20 years in prison and is currently incarcerated in the Jessup Correctional Institution. He began painting after being inspired by the work of his fellow prison artists. His vibrant acrylic portraits of inmates help tell the story of his own struggle and the struggles of his comrades in exile.- Gallery talk by muralist, painter and outsider art authority Dr. Bob Hieronimus

- refreshments provided

-

Goodbye, Heart of Darkness

This has been a bit of a summer of upheavals for me, personally, so I hope you readers won’t mind a personal note to this post. After two years of having the privilege to work with the teachers and student scholars of the JCI Prison Scholars Program, I’ve finished my last class – at least for a long while. I had been planning on taking a break from teaching this Fall to focus on some other work (including some writing on criminal violence in the US that will eventually show up in the drafts available to patrons) already, but as it turns out I will not be living in Baltimore after that – I will be taking up a post with the Centre for Conflict Resolution in Cape Town, South Africa.

I walked out on my last day, somewhat anticlimactically, since a lot of folks had already left to not lose their place in the dinner line. But at the very least Mr. Greco, Jamaican Eddie, Mr. Epps, Craig Muhammed, Kelly, and Mr. Horton had hung around to chat, like they usually do. I told them I hoped that if I came back to Baltimore in four or five years, that the program would still be going and I could teach again – though I hoped I wouldn’t see any of them in my classes. And I tried, and failed, to master the “snap” one last time.

While my departure from JCIPSP was not really planned, I suppose it’s fitting that I’m leaving just after completing my summer course on the wars in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Ever since Conrad used the phrase “heart of darkness” to refer to the Congo, it’s been the lazy go-to label for any place where affluent, mostly white folks go to try to help the natives and have their faith in humanity tested, including prisons (though I see the tagline on the article profiling Mikita Brottman’s work has been changed, which is cool).

The thread that runs through my own work, and links studying the wars in Congo and teaching in prisons, is a resistance to that sort of thinking about the people who live in war zones (declared or not quite declared). First and foremost, people are people. Warlords and child soldiers, prisoners and guards, civilians and politicians, all make decisions for reasons that are ultimately understandable if we take the time to look at them. Back when I started studying African security issues seriously, I had lunch with an old mentor and was describing the situation in the DRC to him, and his response was “sounds like they need some adult supervision.”

We haven’t spoken since.

The reason I used Stearns’ book for this course (even though it’s a bit less systematic and detailed than the gold standard on the war, Prunier’s massive Africa’s World War) is precisely that it humanizes the conflict for people who are learning about it. Stearns builds his book around the narratives of people who were caught up in the war – some of them were leaders of brutal military units or equally brutal paramilitaries, some were businesspeople, some were child soldiers, or just civilians trying to get by. But throughout the book he makes a point of showcasing people’s stories of why they did what they did. Civilian members of a small religious sect that stayed near where their founder had set up worship. Kinyarwandan-speaking Congolese whose parents urged them to cross the border and become child soldiers. A Hutu police chief during the genocide who kept his position while their colleagues engaged in mass murder, but maintained his own clean hands – then went to war against the new Rwandan regime.

I did my best, with mixed success, to replicate that approach in the class itself. We talked a lot about the personal narratives in the book, and how it related to other kinds of violence. Some of the guys would bring up ways in which the situation of people in DRC reminded them of their own situation, as guys who had gotten involved in violence here in the US. My big regret from the class is that I never quite managed to dig deeply into those stories and connections – we very quickly tended to end up relating things from the DRC to other large-scale current events the guys saw parallels to – Gaza, Ukraine, Iraq, or Ferguson. It seemed sometimes that they were more comfortable talking about those sorts of “current events” – or perhaps deep down I was more comfortable talking about them. If I’ve learned anything from my time teaching at JCIPSP, it’s that really listening to your students is much tougher than it seems. I’d walk in every class intending to do it, and find at least three points at which I’d failed when I did my internal post-mortem on the drive home. I also tried to give them writing assignments that took a similar approach of bringing big ideas down to earth through relationship with relatable stories (a history-teaching technique imparted to me by my colleague Rachel Donaldson) – asking them, e.g., where they would go and what they would bring if war had broken out where they lived before coming to prison. Not everyone did the writing assignments, but I’ll post some of them as I transcribe them.

If there were two bits of the class that made me feel like I’d done some of my job correctly, here they are. First, there are a lot of African immigrants here in Maryland, many of whom left to avoid wars at home. A good number of them have become guards at JCI, it seems. Several times, guys in my class told me that a guard had seen them carrying a copy of the book, or heard them talking about DRC (or Liberia, which I discussed in a previous class) and expressed warm surprise that my students actually knew something about the guards’ homelands. And the students told me that – like most Americans – many of them hadn’t really known much about what was going on in Africa before taking classes with me, so it gave them a new understanding of the situations a number of the guards were coming from. I’m told that this has led to a number of good conversations. So, if I’ve helped some of my students and some of the guards improve the humanity of their relationships a little, that’s at least as important to me as if anyone remembers the difference between the RPF and the RCD a year from now.

Second, somewhat weirdly, I think I may have humanized some of the decision-makers in foreign policy a bit. One constant in our classes has been the prevalence of conspiracy theories. This is especially true when you’re talking about the DRC and its neighborhood, where Mobutu was in fact put into power by a CIA conspiracy (among other conspirators), and where one of the main players in the war, the Rwandan Patriotic Front, began its life as a conspiracy within the Ugandan military, backed by the US. So there’s a tendency for a lot of my students to want to find the way that the US created the war (or any other problem) in order to get money or kill non-whites. By the end, I think I managed to convince at least some of them that greed and racism are real drivers of stuff in the world, but it’s not always that simple – just as the people in Congo aren’t Conrad’s monstrous savages, the powerful actors involved are often venal or misguided or biased, but rarely vampires. If you go hunting for the monsters, you’ll miss the more systematic aspects of what goes wrong in places like Congo – or Baltimore or Ferguson, for that matter.

In the end, I am not sure how much I helped – and you’ll probably be better served by reading some of my students’ writing than this long and self-indulgent reflection. I’m always a little bit embarrassed by the kind words and certificates that are handed to me at the end of classes that I teach. This semester, knowing I was leaving, Mr. Greco also made up a sort of “lifetime achievement” certificate that honors me for “standing in the gap against international, national, and local crimes of police, armed forces and terroristic brutality; and for teaching those who society devalues.” I’m not sure I do any of that. I’m pretty sure I haven’t stopped any police violence or reformed any paramilitaries lately.

And I’m not sure even about the last part. We struggle, in this program, with the concept of “teaching.” It is very possible that we are fooling ourselves into thinking we have done real good, real pedagogical work in the deepest, most empowering sense of the term, when really all we have done is have intense experiences for ourselves. That’s the danger of the Heart of Darkness paradigm for liberals. There’s a more charitable read of Conrad’s work, where Congo isn’t the titular heart of darkness itself, but a place where the darkness at the heart of European colonialism is revealed, and destroys the world around it in the revelation. But if you read it that way, and congratulate yourself on your anti-racism, you risk missing the fact that even that reading turns the Congolese from savages into bit players in the white journey of self-actualization and improvement. I mean, it’s an upgrade, but, still… enh. We are all trying our best to make this project about more than our personal journeys, but we probably only intermittently succeed.

The other thing is the bit about society devaluing men in prison. This is sort of true, and sort of not. I have already talked a lot about the way in which the communities from which incarcerated men tend to come are profoundly disconnected from the community that I live in, and that many of you readers live in. I know many of the guys talk about being cut off from their families. I’m terrible to get on the phone, and I know that for people who can’t email me, that often makes my commitment look less than steadfast. I know these things matter for building those human relationships and I fail as often as anyone else, if not more so. But I also see folks waiting in the visiting room every time I go to teach. Incarceration has a profound effect on those communities I’m not a part of, and the loss of the value of the men in prison is keenly felt there. If “society” doesn’t value people in prison, we’re using “society” in a way that implicitly excludes a lot of people who live only a stone’s throw away from me here in Baltimore. And highlighting the way that the “society” I go home to when I’m done teaching in the prison is deeply and constantly involved in a process of exclusion and devaluation.

Hello, heart of darkness.

-

Prison Abolition, Reform, and End-State Utopias

(Cross-posted from anotherpanacea.com)

Recently I’ve been thinking about a book by Erin McKenna which I read as an undergraduate: The Task of Utopia: A Pragmatist and Feminist Perspective. I read it then because it promised to bridge the divide between my favorite genre, science-fiction, and my interest in philosophy. But the book profoundly changed me, and I’m always surprised that others haven’t read it; it feels like a classic. Using John Dewey’s work, McKenna articulates what she calls a “process model” for utopias, whereby we distinguish disputes about “end-states” from judgments about the “ends-in-view.” And this has always deeply affected my politics and thinking about political philosophy. I tend to think that far too many theoretical and practical divides are reducible to debates about end-states, such that even though progressives, libertarians, and anarchists all share the same criticism of some aspect of the state, they cannot work together. Usually these disputes are bolstered by philosophical and theoretical apparatus. The divide between prison reformers and abolitionists, for instance, is understood by abolitionists through the lens of Foucault’s critique of the 19th Century reformers, whose reforms, though sometimes well-meaning, only intensified incarceration by making it more exacting and effective while empowering the reformers. Meliorists who merely protests injustices or inequities but do not loudly call for the absolute abolition of prisons are falling into a “carceral logic” by which prisons will inevitably be preserved in all their evils.

Where I find McKenna helpful is, first, in her claim that end-state disagreements tend to be associated with masculine utopias, while feminist utopias emphasize ends-in-view (which jives with my readings of the relevant science-fiction utopias, and also of polital theories that have utopian elements), and second, in her Dewyan typology for judging ends-in-view. According to McKenna’s reading of Dewey, there are five criterion (five questions, really) by which we can judge an end-in-view:

Where I find McKenna helpful is, first, in her claim that end-state disagreements tend to be associated with masculine utopias, while feminist utopias emphasize ends-in-view (which jives with my readings of the relevant science-fiction utopias, and also of polital theories that have utopian elements), and second, in her Dewyan typology for judging ends-in-view. According to McKenna’s reading of Dewey, there are five criterion (five questions, really) by which we can judge an end-in-view:- Does it promote education and participation? Will the people participate in decision-making and goal formation?

- Is it realistic? Does it acknowledge our embeddedness in constraining contexts?

- Is it flexible? Can it be modified as new conditions emerge?

- Does it aim to develop capacities and abilities, not just states of affairs?

- Does it open up possibilities or close them off? Does it promote plurality or isolation? Cooperation or competition? Power or paralysis?

Halden Prison in Norway This is where I find abolitionism frustrating: the project of prison abolition seems like an end-state rather than an end-in-view. It deliberately ignores (1) the wishes of victims, citizens, and even many of the incarcerated (all of whom are understood to be duped and epistemically blinded by the ideology of carcerality unless they adopt abolitionism.) It doesn’t start with our current carcerality and work away from it, but rather starts with a rejection of the current context and the constraints it creates (2). It’s inflexible (3) in the sense that it does not allow that some limited carcerality (a la Norway?) might still be reasonable. Though there’s the sense that that is the direction that abolitionism must proceed, it does not currently emphasize the development of the skills and abilities (4) that alternatives to incarceration would require. And though it does aim to foreclose carcerality forever, I do think abolitionists are most concerned to promote plurality, cooperation, and empowerment (5) for some of the most dominated people in our world today, which is why I can’t help feeling the pull of abolition even as the other objections I mention raise red flags.

Meliorism, on the other hand, has all the problems that the abolitionists describe. Reformers work with and within the system to resist it, which requires all sorts of rhetorical and practical compromises. By chipping at the edges and living too comfortably with “constraints” and “realism,” (2) meliorists leave the status quo mostly untouched. We adopt democratic projects and processes (1), but leave the fundamental injustices in place. We develop capacities (4) but usually we can’t create the institutions and conditions (5) where those capacities will be actualized. We are, at base, flexible (3) with evil, and thereby compromised by it, while the righteous know that evil requires inflexibility and even sacrifice.

Angela Davis puts it this way at the start of Are Prisons Obsolete?:

“As important as some reforms may be-the elimination of sexual abuse and medical neglect in women’s prison, for example-frameworks that rely exclusively on reforms help to produce the stultifying idea that nothing lies beyond the prison. Debates about strategies of decarceration, which should be the focal point of our conversations on the prison crisis, tend to be marginalized when reform takes the center stage. The most immediate question today is how to prevent the further expansion of prison populations and how to bring as many imprisoned women and men as possible back into what prisoners call the ‘free world.’”

No reformer wants to “produce the stultifying idea that nothing lies beyond prison,” but much of the rest of Davis’s book is devoted to the claim that reform is inextricable from that consequence. Ultimately, she equates prison reform with the absurdity of “slavery reform.” America’s prisons are historically and in current practice entangled with the Black Codes, the convict-lease system, Jim Crow, sexism, and antiblack racism; therefore, reformers are merely (hopefully unknowingly) fluffing the pillows while white supremacy and patriarchy is maintained:

If the words “prison reform” so easily slip from our lips, it is because “prison” and “reform” have been inextricably linked since the beginning of the use of imprisonment as the main means of punishing those who violate social norms.

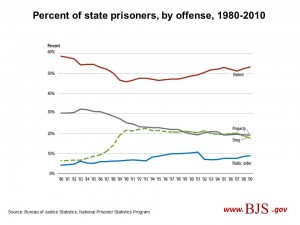

Yet consider: Davis assumes that the majority of the increase in incarceration has been driven by the drug war, and that alternatives to incarceration will foreground drug treatment and decriminalization of drugs. In fact, though the largest group of arrests are tied to drug use, the largest group of prisoners are incarcerated for violence; this reflects sentencing differences and the kinds of treatment diversion programs for which she calls. There’s good evidence that the drug war, poverty, and racist policing produce some of that violence, but not all of it. Plus, prison populations are already shrinking, but at least some of this decline is due to the increase of post-release strategies that export carceral logics into a parolee’s (or even an unindicted suspect’s) everyday life. The goals of decarceration can fall into the logic of carcerality as easily as the goals of reform. So how much really separates reformers from abolitionists? A reformer might call for the restoration of prison education and voting rights, for the creation of schools that teach rather than prepare students for prison, for decriminalization and treatment of drug abuse, for poverty-reduction and racial justice, while still thinking that certain kinds of violence should lead to coercive detention, that restorative justice has dangerous implications when applied to cases of sexual assault or organized violence.

And we see similar strands in Davis:

“In thinking specifically about the abolition of prisons using the approach of abolition democracy, we would propose the creation of using an array of social institutions that would begin to solve the social problems that set people on the track to prison, thereby helping to render the prison obsolete. There is a direct connection with slavery: when slavery was abolished black people were set free, but they lacked access to the material resources that would enable them to fashion new, free lives. Prisons have thrived over the last century precisely because of the absence of those resources and the persistence of some of the deep structures of slavery. They cannot, therefore, be eliminated unless new institutions and resources are made available to those communities that provide, in large part, the human beings that make up the prison population.”

A reformer sees nothing objectionable in those prescriptions, wants to join with the abolitionists for all their ends-in-view and put off the day when end-states might divide us. When the day comes that prisons truly are obsolete, reformers hope that they will be able to see that, too. But who really thinks that today is that day? Not Davis, who wants to “solve social problems” before throwing open the prison doors. In the meantime, why can we not work together to shrink and ameliorate the torturous institutions we all abhor? Why isn’t the reified distinction between abolition and reform as meaningless, today and for the foreseeable future, as the division between those who want to live in a world where the state withers away (Engels) and the world where the state has become small enough to drown in a bathtub (Norquist)? (Norquist now favors some decarceral strategies: is he an ally or an enemy?) If ends-in-view divide us, we must deliberate, compromise, and fight; so long as we are only divided in our utopias, why not collaborate?

-

Shelby Norton’s experience working at JCI

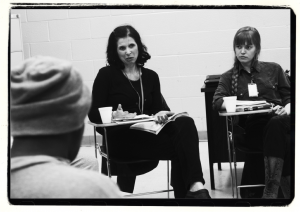

Friday June 13, 2014: My name is Shelby Norton and I am an Interdisciplinary Sculpture student at MICA. During my freshman year I took a class called Community Arts Partnership (CAP): Finding Baltimore. An advocate for restorative justice came to talk to the class with a psychologist from the city jail. He

liked what we were doing in the class and arranged for us to meet with the art group at Patuxent Institution in Jessup, MD. It was a pivotal moment for the way I view art and my career path. To this day, Dr. McCamant is a dear friend and mentor. I worked with him for a year through the CAP program at the Baltimore City Detention Center in the ward of psychiatric health as an art therapy intern building community. The jail was in unrest with Black Guerilla Family (BGF) scandals, and Dr. McCamant had been petitioning against some of the warden’s unjust decisions when he was asked to resign from that position. He continued to work for the state at JCI, but I didn’t work with him for a full year. I was interested in getting back into the line of work, but was out of touch with Dr. McCamant. I heard that a MICA professor, Mikita Brottman, was doing groups at JCI, so I contacted her and asked to be her intern. After it was approved, I invited both Dr. McCamant and Mikita to an art opening at Gallery 405 where they met and discussed working together.

liked what we were doing in the class and arranged for us to meet with the art group at Patuxent Institution in Jessup, MD. It was a pivotal moment for the way I view art and my career path. To this day, Dr. McCamant is a dear friend and mentor. I worked with him for a year through the CAP program at the Baltimore City Detention Center in the ward of psychiatric health as an art therapy intern building community. The jail was in unrest with Black Guerilla Family (BGF) scandals, and Dr. McCamant had been petitioning against some of the warden’s unjust decisions when he was asked to resign from that position. He continued to work for the state at JCI, but I didn’t work with him for a full year. I was interested in getting back into the line of work, but was out of touch with Dr. McCamant. I heard that a MICA professor, Mikita Brottman, was doing groups at JCI, so I contacted her and asked to be her intern. After it was approved, I invited both Dr. McCamant and Mikita to an art opening at Gallery 405 where they met and discussed working together. -

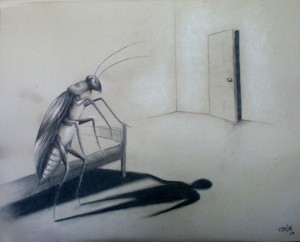

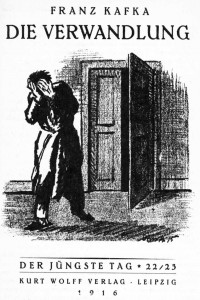

July 23: Final Class on Kafka

There’s always something a little bit sad about the last class of the semester. I’m leaving for a relaxing summer vacation, and the men are… stuck exactly where they always are. In a normal academic environment, the summer is a time for renewal and regeneration – metamorphosis, in fact – but at JCI all seasons are pretty much the same.

There’s always something a little bit sad about the last class of the semester. I’m leaving for a relaxing summer vacation, and the men are… stuck exactly where they always are. In a normal academic environment, the summer is a time for renewal and regeneration – metamorphosis, in fact – but at JCI all seasons are pretty much the same.This week we discussed Part III of the story, and ended up having a long debate about whether or not “insect” Gregor bore any physical resemblance to “human” Gregor. Some of the men imagined “insect” Gregor to have “human” Gregor’s face, which isn’t something described by Kafka. I thought is was probably their own projection on to the story. The men were especially interested in analyzing the story’s “final meaning,” especially the significance of the three bearded lodgers (the “three wise men,” as Mr. Drummond referred to them). We also discussed how, once Gregor is dead, his parents are referred to as “Mr. and Mrs. Samsa” instead of “the Mother and the father. Mr. Luskey suggested this may be due to the fact that they are no longer figures in Gregor’s narrative – in fact, now Gregor is only a figure in the narrative of others – people, indeed, just like us.

-

July 16: Advanced Literature / Kafka

This week, we discussed Part II of Kafka’s “Metamorphosis.” For their homework, I’d asked the men to imagine themselves as Gregor’s sister Grete, and to write a letter to their best friend, giving an account of what’s been happening in their life. Here’s part of Mr. Gross’s response: “Guten Tag Ava. My family is experiencing some troublesome times which explains why I haven’t been able to visit you. Remember how you used to say my brother was creepy? Well, you’re not going to believe this, but now not only is he creepy, he’s also a crawler. He’s turned into a full grown bug. As for me sharing this with you, I should also tell you that only father, mother, the chief clerk and myself know about this, so please keep it a secret because I don’t want our house to turn into an insect zoo.” We’ll be discussing Part III in our final class next week.

This week, we discussed Part II of Kafka’s “Metamorphosis.” For their homework, I’d asked the men to imagine themselves as Gregor’s sister Grete, and to write a letter to their best friend, giving an account of what’s been happening in their life. Here’s part of Mr. Gross’s response: “Guten Tag Ava. My family is experiencing some troublesome times which explains why I haven’t been able to visit you. Remember how you used to say my brother was creepy? Well, you’re not going to believe this, but now not only is he creepy, he’s also a crawler. He’s turned into a full grown bug. As for me sharing this with you, I should also tell you that only father, mother, the chief clerk and myself know about this, so please keep it a secret because I don’t want our house to turn into an insect zoo.” We’ll be discussing Part III in our final class next week. -

Why don’t you ever see TV interviews with inmates?

interesting article from The Atlantic.