The men were not in a good mood today – and understandably so. According to a recent memo, the new DPSCS Secretary has decided that, from December 1, in order to curb the passing of contraband, there will be no more physical contact during prison visits–no touching, no kissing on the mouth, no hugging. What will this mean for the fathers of young children? Men with elderly parents? Newly-married couples? It’s difficult to imagine.

Though not, perhaps, for George Orwell. Our final book of the semester is Animal Farm. Officially, it was Mr. Drummond’s choice, but a number of the men mentioned they’d heard about the book and wanted to read it. A couple of them, like me, had read it a long time ago but were happy to read it again. I introduced the book in class and discussed Orwell, his life and work.

Though not, perhaps, for George Orwell. Our final book of the semester is Animal Farm. Officially, it was Mr. Drummond’s choice, but a number of the men mentioned they’d heard about the book and wanted to read it. A couple of them, like me, had read it a long time ago but were happy to read it again. I introduced the book in class and discussed Orwell, his life and work.

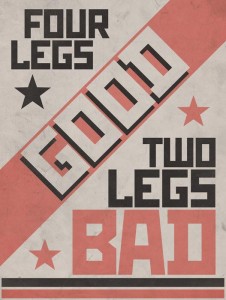

In a way, I wish I hadn’t brought up the notion that Animal Farm is an allegory, because although it’s interesting (and to some degree inevitable) to think about it allegorically, I also think there’s a lot to be said for paying attention to the story as a story. We began reading the book aloud in class. Comments made by Mr. Simpson and Mr.Barnett brought to my attention the fact that these animals are already domesticated and institutionalized. Their revolution is already doomed to failure. The very concept of revolution, in fact, is a human concept. Animals don’t get together and rebel. In the wild, different species are natural enemies (and a lot of these species are actually man made hybrids and don’t even exist in the wild).

It was interesting to discuss Orwell’s prose. The pictures he paints are vivid enough to make Mr. Arey laugh out loud, which is a good touchstone in my opinion, though it that doesn’t seem to take much. The prose is almost invisible, but in a different way from Steinbeck and Hemingway’s prose. Hemingway’s sentences were so short, they called attention to themselves; Orwell’s never do. “Good prose is like a window pane,” wrote Orwell in an essay entitled “Why I Write,” meaning that good writing should allow you to see straight through to what is being said, without getting in the way. It should be clear and transparent, and allow you to see what is happening on the other side. Although some of the language here may be slightly technical or a little archaic, it’s generally perfectly clear.

The attack from Mr. Jones and the other farmers is the first sign that the animals are going to have divided loyalties. This probably won’t be the only attack from the humans, so there’s going to be a need to concentrate on defense. But there’s also a need to keep their own ranks in order. And then there’s Snowball and his Utopian windmill. If it works, it could lead to a three-day working week—and Snowball’s a smart pig. But Napoleon seems even smarter, since he’s managed to privately train a pack of savage attack-dogs as his own private army to run Snowball out of town. Snowball is quickly forgotten, and before long the windmill is being discussed again, only this time it’s Napoleon’s idea.

The men noted that the pigs are taking advantage of most of the other animals on the farm, realizing that they’re basically very good, but very gullible. Nobody has any real access to information, so rumors fly around and nobody knows who to trust, or even what really happened during the Battle of the Cowshed. The situation is in flux, and all the animals are anxious and excited, and in situations like this, manipulators can take advantage of the weak. It’s notable how dumb and ignorant so many of the animals seem, how much they’re at the mercy of the pigs, who are the only ones with any real knowledge, since they’re the ones who can read and write. And of course, the pigs are on top because the revolution was started by one of their own: Old Major, the heroic pig who revived the philosophy of Animalism.

If the pigs represent political leaders and the animals represent the ordinary people, Orwell does not have an especially good opinion of either. With this cast of characters—and with attributes like greed, selfishness, fear and hunger for power—it’s difficult to imagine any political situation actually working. No wonder we’re in such a mess. In reality, animals seem to govern themselves much better than we humans do.