This semester, we’re trying something different in Advanced Literature. After putting the men through Conrad, Melville, Poe, Shakespeare, Nabokov, etc., I’ve decided to turn the tables and let them select the books for a change. The book we’ve started with is Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck, chosen by Mr. Gross. The book is really not a favorite of mine. I don’t like Steinbeck’s sentimental idealization of the poor, nor do I lie his action-oriented plots. I find his work very macho, and I complained about it in class.

Later, I regretted my complaints, especially knowing how much the book means to Mr. Gross. Now that I know how important it is to a man whose opinions I respect, I’m going to work a little harder to go beneath the surface and lay aside my knee-jerk reactions. After all, I believe (or I like to believe) that’s what a lot of the men did with some of the books I chose, like the Edgar Allan Poe stories that drove Mr. Fitzgerald so crazy, or Lolita, which so many of the men found so difficult to read because of their distaste for Humbert Humbert. But they knew the book meant a lot to me, so they struggled and went ahead despite their distaste, and many of them ended up finding something memorable in these books. Or, at least, they said you did. I hope they did. I like to think they did.

So when reading Of Mice and Men, I thought to myself, what does Mr. Gross see in this book? What does Mr. Peters see? And when I tried to see it through the men’s eyes, I found there was more going on in the story than I previously wanted to acknowledge—even, as Mr. Arey pointed out, psychologically.

In the scene we read this week, Lennie lets Candy in on his and George’s plan to retire on their own farm and breed rabbits, and it turns out Candy’s actually got savings of his own and asks to join them. The plan that had always been a fantasy suddenly, for a short while, comes to life and becomes real. Curley’s wife always seems to be hanging around Slim, and Curley loses it. Slim stands his ground, so Curley turns on the guy who seems to be the underdog—the big dumb semi-mute Lennie. This is when we see Lennie in action. He may not be smart, but he’s as strong as an ox and as stubborn as a bulldog. Once he starts, it’s almost impossible to get him to stop. He’s almost like an animal in that sense–dangerously unpredictable.

This section shows us how tough these men have it. Like Candy’s old dog, they go on until they die, with no one to put them out of their misery. We sense the misery and physical pain of the workingman’s life, the male competition and camaraderie, with no entertainment but drinking and fighting, playing cards and tossing horseshoes. In this sense, the bond between George and Lennie seems to be vital and unusual. They protect each other, rather than competing. George could use Lennie like a tool, but instead he tries to look after him, to stop him from getting into trouble. They both need each other, and have come to rely on each other. But George has something that Lennie doesn’t have, and that’s someone to look after and care for. Looking after Lennie gives meaning to George’s life. Lennie copies George in every way, which is why he’s always looking for his own creature to care for – whether it be puppy, mouse, or rabbit. It seems ironic that in his own mind, Lennie sees himself as a gentle, vulnerable creature, easily hurt. In this section, we see how to others, he can suddenly become terrifying.

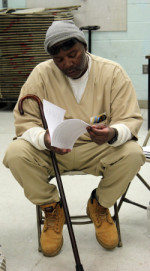

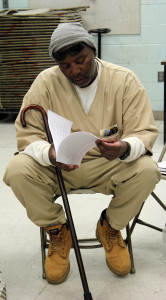

Reading from The Maximum Security Book Club and Q&A at the Enoch Pratt Library on June 15, 2016, with (l to r) JCI Scholar Vincent, Baynard Woods, Correspondent for the Guardian and writer for the City Paper, Glennor Shirley, Maryland State Prison Librarian, and JCI Scholar Mikita Brottman. You can listen to interviews with Mikita and Vincent at:

Reading from The Maximum Security Book Club and Q&A at the Enoch Pratt Library on June 15, 2016, with (l to r) JCI Scholar Vincent, Baynard Woods, Correspondent for the Guardian and writer for the City Paper, Glennor Shirley, Maryland State Prison Librarian, and JCI Scholar Mikita Brottman. You can listen to interviews with Mikita and Vincent at: