While it may be the middle of July, the JCI Scholars Program has not been as quiet as the website over the summer. Over on our current classes page you can now find links to brief descriptions of the courses being taught this summer, ranging from mindfulness to the environment and many points in between. Check it out, and I hope to have some reflections on the classes from our instructors and students to share here as well.

Category: classes

-

Summer Teaching Schedule (Better Late than Never)

While it may be the middle of July, the JCI Scholars Program has not been as quiet as the website over the summer. Over on our current classes page you can now find links to brief descriptions of the courses being taught this summer, ranging from mindfulness to the environment and many points in between. Check it out, and I hope to have some reflections on the classes from our instructors and students to share here as well.

-

Don’t Call it a Comeback

It wasn’t too long ago that I was expecting not to teach for the Scholars Program anymore. Things don’t always work out as you expect! But, as of this past Wednesday, I was glad to find myself back in prison. Wait… well, you know what I mean.

There have been some changes since I was last inside. Our old “inside coordinator,” Vincent Greco, has since been released – great for him! But an adjustment for the program – fortunately, one of our long-term students has stepped up and seems to be doing a solid job of things. I’ve gotten letters from a couple of guys who had been in my classes with return addresses from other facilities, but I also saw some familiar faces on my way in.

Things are a little up in the air, so this summer I’m only teaching a short course – four sessions on non-violent resistance (to war) based around the War Resisters’ International Handbook for Non-Violent Campaigns. Since we hadn’t met before, we started class out with just some general discussion of what violence is, and why one might at least sometimes decline to use it in pursuit of a goal. I got to go over some of the Chenoweth and Stephan data on the success of non-violent campaigns in response to the entirely unsurprising view that some of the guys expressed that clearly, whichever side of a conflict was more willing to use violence (and more extreme violence) would win. I’m not sure they’re convinced – apparently they had a class last semester with a guy who taught a course on why violence is inevitable (I leave for a few semesters…).

Running the class itself brought me back to the familiar dynamic these classes often have. Unlike courses I’ve taught in “normal” university settings, the guys in the class are much less willing to let anything I say go unchallenged (itself a challenge when we can’t go to the internet on someone’s laptop to resolve a question), and they are much more eager to pull the class off into their own directions. Which sometimes leaves me feel like I’m just barely riding the wave rather than running a class, but comes from an interesting and good place, I think – we end up talking about whether Mormons count as secessionists because someone has noticed that I didn’t exactly define what counted as successful secession when I was discussing the data… so it represents people engaging with the material, even if often in a way that comes out of left field from the perspective at the front of the class. Oh, and of course, we had at least two conspiracy theories floated.

I’m looking forward to our next session.

-

Teaching and Learning in a Maximum-Security Prison

When I tell people that I volunteer teach at a maximum-security prison, many people nod and tell me “that’s cool,” and some compliment me for being “generous.” But few understand what a deeply gratifying, enriching, and inspiring experience it is.

I wasn’t a newcomer to the prison environment. I’d been familiar with several prison visiting rooms over the course of the 17-year wrongful incarceration of my childhood friend, Marty Tankleff (who was eventually exonerated in 2007), and we had discussed prison life at length over the years. For several years I have also been teaching a course at Georgetown called “Prisons and Punishment,” which included visits to Jessup Correctional Institution and the D.C. Jail. And I had the surreal experience of playing tennis with the “inside team” at San Quentin State Prison in California, which I wrote about in Sports Illustrated. But these were always short visits in a controlled setting.

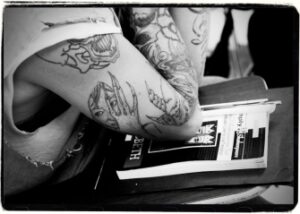

I started teaching at Jessup in the Fall 2014 semester because I wanted to have more sustained, open, and genuine interaction with inmates. I also wanted to provide an educational opportunity to a group of people who have largely been forgotten by society. Research has clearly shown that inmates who further their education while incarcerated will improve their behavior within the prison environment and will be less likely to pursue a life of crime after their eventually release. The Jessup Scholars Program provided an ideal opportunity to create a productive educational environment in a classroom setting with minimal staff supervision, with a group of students who chose my class and were eager to learn.

The class was the same as one I have taught at Georgetown for many years, called “Fascism and Extremist Movements,” which I was also teaching in Fall 2014. In this course, we spend the first half of the semester examining historical fascism, and in the second half we focus on different contemporary extremist movements. After some deliberation, the prison administrators decided that a course entitled “Fascism” might send the wrong message in a prison setting (after all, gangs and other extremist groups might think it is a “how to” course), so they suggested that I change the title to “World History,” which I came to embrace.

As the weeks went by, I was teaching the same material in both places—on Mondays at Georgetown with 16 students, on Tuesdays at Jessup with 35 students. Although obviously the level of academic preparation was different across the two groups, I was continuously impressed by the high-quality discussions maintained by the majority of my Jessup students.

We had a particularly enlightening conversation about the concept of charisma, in which we contrasted Max Weber’s rather strict definition that refers to the “exceptional sanctity, heroism or exemplary character of an individual person” as distinct from the common usage in political and popular discourse that essentially refers to “popularity.” We then discussed the role of charisma in the appeal and power of historical figures such as Hitler and Stalin (whose charisma was not personal, but rather deflected into the impersonal institution of the Communist Party), as well as more “positive” leaders such as Nelson Mandela and Martin Luther King, Jr. And we debated whether modern-day politicians like Bill Clinton or Barack Obama meet the Weberian criteria for charisma. Throughout this memorable and engaging discussion, I was astounded by the Jessup students’ knowledge of “world history” and their desire to apply it creatively to the new conception language and framework I had given them.

The students also kept me on my toes by occasionally offering “outside the box” comments that were often insightful, even if sometimes evocative and provocative. For example, when we were contrasting Mussolini and Hitler’s degree of totalitarian control, one student explained the implications of Mussolini being softer on opponents in his midst by analogizing to his experience with the Baltimore underworld, claiming that Mussolini was “like a pimp who falls in love with one of his ho’s and then loses the respect of his followers.” And every once in a while there would be a random comment or question from someone who was quite lost—e.g., after a long discussion of the role of anti-Semitism in German culture, one student raised his hand and asked if German shepherds come from Germany. Overall, though, many of the Jessup students held their own, even by Georgetown standards.

As the weeks went by and my enthusiasm for teaching my “parallel classes” continued to grow, I decided to see if we could make them intersect for a week. So I approached the prison officials about the possibility of holding a joint class session at Jessup. To my delight, they were very accommodating and helpful, understanding the clear educational benefit. My Georgetown students—several of whom had previously taken my “Prisons” class that included a group tour of Jessup—were excited about the opportunity. And, needless to say, my Jessup students were thrilled (and one asked jokingly if we could hold the class at Georgetown instead of Jessup).

In preparing for the joint session, I worked hard to create a format and structure that would make it a productive, effective, and memorable class for all students. The topic we were covering that week was “Right-Wing Extremism in Contemporary Europe.” Given the nearly polar opposite racial imbalances of my two groups of students, this seemed more suitable than the topics of the following two weeks, White-Power and Black-Power extremism.

The main objective of the joint class session was to create a comfortable classroom dynamic whereby the students from both groups could interact in a way that was not only relaxed and respectful, but during which they could momentarily leave behind their vastly different backgrounds, situations, and opportunities, in order to discuss and debate the materials as “fellow students.” I wanted the experience to be more than a mere novelty for both sides. I especially wanted my Georgetown students to appreciate the humanity, intelligence, and determination that my Jessup students bring to my classroom every week. My hope was that it would move and change them, helping them to think differently about “criminals” and “felons” who are so stigmatized—and forgotten—in our society.

The class session was phenomenal. We arranged the chairs in a larger circle, mixed in the Georgetown and Jessup students, and had some light ice-breakers to launch the conversation. Then I divided them into eight smaller groups and had each group tackle a set of core questions about the topic (mainly evaluating how contemporary right-wing movements relate to historical fascism in several different respects). When we returned to the full group, each smaller group was responsible for leading the discussion on a particular question. The time flew by, and the conversation never stopped flowing. The Georgetown students became more comfortable and relaxed, and the Jessup students were able to contribute their insights. For just a short while, my two classes became one, and both sets of students were able to shine.

As someone who has been a professor for well over a decade now, this was without question my most thrilling moment as a teacher. Many of my Georgetown students described it as their most memorable educational experience, and my Jessup students were deeply appreciative to have had the opportunity to share a “Georgetown class.”

The next few sessions at Jessup went smoothly, and we closed out the semester with a wide-ranging discussion of the topic “Fascism in Our Future?” As the final class came to a close, it dawned on me that this remarkable experience was about to end—at least for the Fall 2014 semester—and that I was going to miss this class tremendously.

Before handing out the Jessup certificates of completion to the 35 students in my Fall 2014 “World History” course, I offered my students some final remarks. I told them:

I want to thank you for having inspired me, in three different ways:

1) with your intelligence

I have learned so much from our discussions, from your thoughts and reactions to the readings and debates, and your points of view about human nature, social history, and world affairs.

2) with your sense of humor

We dealt with serious and solemn themes and topics—oppression, genocide, racism—and you were respectful towards me and each other. But you also realized that we learn more when we enjoy ourselves, and your jokes and levity were refreshing. I don’t know if I’ve ever laughed so much in a classroom before, and I really appreciated that.

3) with your courage

I understand that your everyday life here is not easy, and in many ways it is grim and depressing. I know that many of you have made choices in life that you now regret, and that the laws of our society have put you here as a result. But I want you to know that I greatly respect and admire how you have acted with class and dignity, even though there are temptations and pressures that try to push you in other directions. I know it’s not easy, but you have shown me what courage is about.

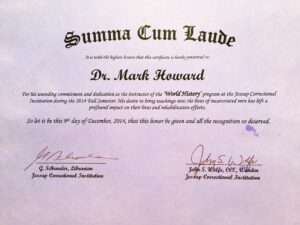

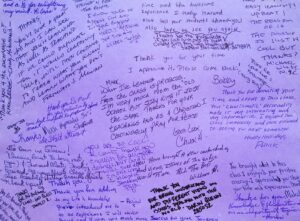

Not to be outdone, they provided me with a nicely-produced “Summa Cum Laude” certificate, and the back of the certificate was entirely filled with hand-written notes of thanks. When I arrived home later that evening, I sat down and read some of the most sincere, profound, and touching comments I’ve ever received. Here are just a few:

“You’ve done a great job, and I can see that you’re learning as well as teaching. If we could duplicate you, it would certainly help. Until then, continue to teach what you know and learn what you don’t.”

“You have brought a new understanding of issues about the entire world to me.”

“Thank you for adding to my life and knowledge. You’ve introduced me to an experience I will never forget, and I wish you much more success on your journey.”

It is now over one month later, and I can say that my journey will soon take me right back to Jessup for the Spring 2015 semester. I’m on sabbatical from Georgetown this semester, as I finish writing a book, but I’ll be in my Jessup classroom every week—teaching and learning.

Marc Howard

Professor of Government and Law

Georgetown University

mmh@georgetown.edu -

Goodbye, Heart of Darkness

This has been a bit of a summer of upheavals for me, personally, so I hope you readers won’t mind a personal note to this post. After two years of having the privilege to work with the teachers and student scholars of the JCI Prison Scholars Program, I’ve finished my last class – at least for a long while. I had been planning on taking a break from teaching this Fall to focus on some other work (including some writing on criminal violence in the US that will eventually show up in the drafts available to patrons) already, but as it turns out I will not be living in Baltimore after that – I will be taking up a post with the Centre for Conflict Resolution in Cape Town, South Africa.

I walked out on my last day, somewhat anticlimactically, since a lot of folks had already left to not lose their place in the dinner line. But at the very least Mr. Greco, Jamaican Eddie, Mr. Epps, Craig Muhammed, Kelly, and Mr. Horton had hung around to chat, like they usually do. I told them I hoped that if I came back to Baltimore in four or five years, that the program would still be going and I could teach again – though I hoped I wouldn’t see any of them in my classes. And I tried, and failed, to master the “snap” one last time.

While my departure from JCIPSP was not really planned, I suppose it’s fitting that I’m leaving just after completing my summer course on the wars in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Ever since Conrad used the phrase “heart of darkness” to refer to the Congo, it’s been the lazy go-to label for any place where affluent, mostly white folks go to try to help the natives and have their faith in humanity tested, including prisons (though I see the tagline on the article profiling Mikita Brottman’s work has been changed, which is cool).

The thread that runs through my own work, and links studying the wars in Congo and teaching in prisons, is a resistance to that sort of thinking about the people who live in war zones (declared or not quite declared). First and foremost, people are people. Warlords and child soldiers, prisoners and guards, civilians and politicians, all make decisions for reasons that are ultimately understandable if we take the time to look at them. Back when I started studying African security issues seriously, I had lunch with an old mentor and was describing the situation in the DRC to him, and his response was “sounds like they need some adult supervision.”

We haven’t spoken since.

The reason I used Stearns’ book for this course (even though it’s a bit less systematic and detailed than the gold standard on the war, Prunier’s massive Africa’s World War) is precisely that it humanizes the conflict for people who are learning about it. Stearns builds his book around the narratives of people who were caught up in the war – some of them were leaders of brutal military units or equally brutal paramilitaries, some were businesspeople, some were child soldiers, or just civilians trying to get by. But throughout the book he makes a point of showcasing people’s stories of why they did what they did. Civilian members of a small religious sect that stayed near where their founder had set up worship. Kinyarwandan-speaking Congolese whose parents urged them to cross the border and become child soldiers. A Hutu police chief during the genocide who kept his position while their colleagues engaged in mass murder, but maintained his own clean hands – then went to war against the new Rwandan regime.

I did my best, with mixed success, to replicate that approach in the class itself. We talked a lot about the personal narratives in the book, and how it related to other kinds of violence. Some of the guys would bring up ways in which the situation of people in DRC reminded them of their own situation, as guys who had gotten involved in violence here in the US. My big regret from the class is that I never quite managed to dig deeply into those stories and connections – we very quickly tended to end up relating things from the DRC to other large-scale current events the guys saw parallels to – Gaza, Ukraine, Iraq, or Ferguson. It seemed sometimes that they were more comfortable talking about those sorts of “current events” – or perhaps deep down I was more comfortable talking about them. If I’ve learned anything from my time teaching at JCIPSP, it’s that really listening to your students is much tougher than it seems. I’d walk in every class intending to do it, and find at least three points at which I’d failed when I did my internal post-mortem on the drive home. I also tried to give them writing assignments that took a similar approach of bringing big ideas down to earth through relationship with relatable stories (a history-teaching technique imparted to me by my colleague Rachel Donaldson) – asking them, e.g., where they would go and what they would bring if war had broken out where they lived before coming to prison. Not everyone did the writing assignments, but I’ll post some of them as I transcribe them.

If there were two bits of the class that made me feel like I’d done some of my job correctly, here they are. First, there are a lot of African immigrants here in Maryland, many of whom left to avoid wars at home. A good number of them have become guards at JCI, it seems. Several times, guys in my class told me that a guard had seen them carrying a copy of the book, or heard them talking about DRC (or Liberia, which I discussed in a previous class) and expressed warm surprise that my students actually knew something about the guards’ homelands. And the students told me that – like most Americans – many of them hadn’t really known much about what was going on in Africa before taking classes with me, so it gave them a new understanding of the situations a number of the guards were coming from. I’m told that this has led to a number of good conversations. So, if I’ve helped some of my students and some of the guards improve the humanity of their relationships a little, that’s at least as important to me as if anyone remembers the difference between the RPF and the RCD a year from now.

Second, somewhat weirdly, I think I may have humanized some of the decision-makers in foreign policy a bit. One constant in our classes has been the prevalence of conspiracy theories. This is especially true when you’re talking about the DRC and its neighborhood, where Mobutu was in fact put into power by a CIA conspiracy (among other conspirators), and where one of the main players in the war, the Rwandan Patriotic Front, began its life as a conspiracy within the Ugandan military, backed by the US. So there’s a tendency for a lot of my students to want to find the way that the US created the war (or any other problem) in order to get money or kill non-whites. By the end, I think I managed to convince at least some of them that greed and racism are real drivers of stuff in the world, but it’s not always that simple – just as the people in Congo aren’t Conrad’s monstrous savages, the powerful actors involved are often venal or misguided or biased, but rarely vampires. If you go hunting for the monsters, you’ll miss the more systematic aspects of what goes wrong in places like Congo – or Baltimore or Ferguson, for that matter.

In the end, I am not sure how much I helped – and you’ll probably be better served by reading some of my students’ writing than this long and self-indulgent reflection. I’m always a little bit embarrassed by the kind words and certificates that are handed to me at the end of classes that I teach. This semester, knowing I was leaving, Mr. Greco also made up a sort of “lifetime achievement” certificate that honors me for “standing in the gap against international, national, and local crimes of police, armed forces and terroristic brutality; and for teaching those who society devalues.” I’m not sure I do any of that. I’m pretty sure I haven’t stopped any police violence or reformed any paramilitaries lately.

And I’m not sure even about the last part. We struggle, in this program, with the concept of “teaching.” It is very possible that we are fooling ourselves into thinking we have done real good, real pedagogical work in the deepest, most empowering sense of the term, when really all we have done is have intense experiences for ourselves. That’s the danger of the Heart of Darkness paradigm for liberals. There’s a more charitable read of Conrad’s work, where Congo isn’t the titular heart of darkness itself, but a place where the darkness at the heart of European colonialism is revealed, and destroys the world around it in the revelation. But if you read it that way, and congratulate yourself on your anti-racism, you risk missing the fact that even that reading turns the Congolese from savages into bit players in the white journey of self-actualization and improvement. I mean, it’s an upgrade, but, still… enh. We are all trying our best to make this project about more than our personal journeys, but we probably only intermittently succeed.

The other thing is the bit about society devaluing men in prison. This is sort of true, and sort of not. I have already talked a lot about the way in which the communities from which incarcerated men tend to come are profoundly disconnected from the community that I live in, and that many of you readers live in. I know many of the guys talk about being cut off from their families. I’m terrible to get on the phone, and I know that for people who can’t email me, that often makes my commitment look less than steadfast. I know these things matter for building those human relationships and I fail as often as anyone else, if not more so. But I also see folks waiting in the visiting room every time I go to teach. Incarceration has a profound effect on those communities I’m not a part of, and the loss of the value of the men in prison is keenly felt there. If “society” doesn’t value people in prison, we’re using “society” in a way that implicitly excludes a lot of people who live only a stone’s throw away from me here in Baltimore. And highlighting the way that the “society” I go home to when I’m done teaching in the prison is deeply and constantly involved in a process of exclusion and devaluation.

Hello, heart of darkness.

-

Reflections from the JCI Criminal Justice Class

It was a great pleasure to be in the company of you and the students. It’s refreshing to be able to let your hair down and just get to know people from the outside. But in prison you always have to be prepared for anything, so it was nice to feel like you were free…As much as people try to separate prisoners from society we are very much the same no matter where we are. There’s always exceptions to the rules, but for the most part we all have the same core thoughts on punishment, desires for our lives, and hopes and dreams for our children. Anonymous, JCI Student

I thought that one of the hardest parts of this journey was going to be removing the label of “inmates” from the inside students. Much to my surprise, that was relatively easy. I learned about my capability to be unbiased and less judgmental. It’s pretty easy to develop judgmental attitudes and become prejudice towards others who are considered by society as “bad” and “dangerous” people; especially living in Baltimore where crime is constantly headlined in the news. I never found it difficult to think of the inside students as anything other than students. Instead, I was able to interact and participate in discussions with the inside men just like I would in any other classroom setting with university students. Sarah, UB Student

My experience with the students was a lot of things. It was very interesting. I was very reluctant to open up at first because of the bias stigma put on me (us) because of my situation being in prison. I do think that the experience as a whole helped me to be more open minded and mindful not to fall into the stereotypes because of my own insecurities. Twist, JCI Student

The respect that was in the room was also very incredible. One thing we talked about before going inside JCI was that we were nervous, and pondering the fact would there be mutual respect? Respect was present at all times in our classes inside, coupled with jokes and laughter which was nice. It was a breath of fresh air to have both seriousness, and humor in the room at the same time. The entire experience was great, and I wish I could go inside every single week and take a class with the JCI students now. John, UB Student

My first experience with the UB students was one of extreme enlightenment. It has been three long years since I last interacted with young men and women within my age bracket from the outside world. It was interesting to witness how similar our perspectives are regarding various different social, economical, and political issues, even though we reside on opposite sides of the societal spectrum. Anonymous, JCI Student

When all the JCI students had left the classroom and the UB students started to walk out through the yard some of the guys were still standing in the middle of the yard. We had then realized that we would never see these guys ever again in our entire life. I remember hearing one of the guys say “Coming from someone who has a life bid, don’t take anything for granted and enjoy your time on the outside.” That statement will always stick with me. I will cherish the fact that I can live my life and do whatever I want to when I want to and not have to be locked up and controlled by an institution. Amanda, UB Student

-

Criminal Justice Group Projects

Visit the criminal justice class page to see examples of students group projects.

-

Advanced Literature 4/16/2014

Guest post from a MICA student, Jess Bither, who joined our class on April 16:

Guest post from a MICA student, Jess Bither, who joined our class on April 16:After everyone introduced themselves, Mikita passed out copies of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Doctor Jekyll and Mister Hyde. Previously, they had been reading Macbeth. I was surprised to hear that they would be allowed to read such a bloody play. I took a step back to analyze my feelings of surprise. High school students are often required to read Macbeth and Romeo and Juliet, so why shouldn’t these grown men be able to read texts that have death, suicide, and murder in them? I must have thought that the mere act of reading would rile them up and perhaps reawaken something…? I don’t think I actually believe that, but for a moment apparently I did. I am still trying to understand my initial reaction. Now, I am asking myself if this means I ultimately believe in the power of art and literature. I have never aligned myself with the camp of thinkers who suggest that consuming depictions of violence makes one more violent, so that is why I am taken aback by my own thoughts.

The more I consider it, the more I find myself thinking that texts that present violence and ethical questions seem especially appropriate in a prison setting where the inmates are told to think about what they did.

Yet thinking about it every hour of every day seems excessive (perverse even). Never thinking about it is frowned upon as well (at least from the POV of those on the outside). So how much is enough, and how much is taboo? -

Violence (5/2/14)

So, at the last Violence class, we were talking about both a section on the rise of the Black Panther Party (from Black Against Empire) and on the early inroads of militarization into police forces (from Rise of the Warrior Cop). A few interesting things came out of the conversation.

First, what ended up being the first question was, “why aren’t we talking about violence in prisons in this class?” Good question. The best answer I could give the guys was that research on violence in prisons is pretty sketchy (at least in the US), and so I was not in a position to teach anything about it. Actually, I am quite interested in it, but am trying to get my ducks in a row on how to actually conduct research. Unfortunately for researchers, the Maryland Department of Public Safety does not currently permit interview research in correctional facilities (and cannot guarantee confidentiality for mail surveys). I did invite them to talk about it in class, but no one volunteered. I also invited them to write about it, so let’s see.

Second, while I did try to keep bringing it back around to the material for the class, the conversation they kept wanting to bring it back around to was the issue of what violence is, particularly the concept of “structural violence.” Unsurprisingly perhaps, most of the folks in the room were pretty friendly to the idea of structural violence, though we did have some interesting discussions about whether there was a need to draw the line somewhere (so that not everything bad is violence), and about how to understand “local” power imbalances – e.g., one (white) student was skeptical that black prejudice against whites is never backed up by power (meaning it’s not “racism” in the way that academics tend to use the term), because he’d been beaten up a few times when visiting a black girlfriend in her neighborhood. So we had a lively debate about that (there were divergent theories about why I don’t get beaten up when I bike my daughter to her school in Park Heights).

Third, we talked a bit – and some of the guys had been in either my class on James or Josh’s on Arendt – about the Panther’s use of violence. As Mr. Jihad pointed out to me, it’s telling the story a bit unfairly to characterize the Panthers as a “violent organization,” but it was important to their role that they were at least willing to threaten and use violence in a way that other groups weren’t. Newton’s analysis of the need for armed resistance is in line with the Marxist analysis of the lumpenproletariat – the proletariat has a lot of (potential) revolutionary potential if it can become organized, because it can down tools, break the machines, stop working, etc. The bosses need the workers! The problem for unemployed inner-city blacks at the time of the Panthers was that many of them lacked even this kind of power – they were lumpenproletariat in the Marxist analysis, outside the class struggle. So, on the one hand, the idea that they need to assert themselves via violence is sharp. On the other hand, there’s a reason that Marx (unless I’m misremembering) identified the lumpenprotetariat as the “dangerous classes” – violent, and a tool particularly of nobility and financiers because they share a lack of productive role in the current system. The concern is essentially that the violence of the lumpenproletariat cannot or will not be turned to revolutionary ends, but only lets them serve as thugs for existing power structures. Seen through the lens of Arendt on totalitarianism, there’s the worrisome possibility that violent action by disenfranchised groups may not be aimed at supporting the powers that be, but may end up serving those ends by creating a kind of ‘reaction formation’ of state repression. This is all very impressionistic, but the roots of US police militarization in reaction to the unrest of the 60s makes it suggestive. We also had some splits there – some folks arguing that repression was the inevitable result of non-nonviolent action, while others supported “diversity of tactics.”

Finally, Josh called me out in the class on the way that the concept of privilege interacts with questions about whether, e.g., it’s helpful to analyze black-America-in-general as a kind of internal colony of white-America-in-general. But I’ll probably have to get to that later.

-

Violence (4/18/14)

So, the Violence class. I’ve wanted to teach a course like this for a while, for two reasons. First, it’s a matter of professional interest to me – especially to look at violence as a phenomenon that cross-cuts issues that are often academically stove-piped (e.g., war, psychology of trauma, domestic violence). Second, it’s an issue that I thought would be of particular interest to our students, and on which they might have some important insights to share.

This past Friday, our topic was sexual violence. We were reading (/should have read) some excerpts from Brison’s Aftermath, along with a USIP Special Report on the motivations of Mai Mai militia members who commit rapes in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Griffin’s “Rape: the All-American Crime.” We’d also just finished a session on “terror,” where we read Scarry’s chapter on torture – with the intent that there would be some links between her analysis of the silencing and identity-destroying effects of torture and those effects of sexual violence on women, particularly the way these effects impact women beyond the class of direct victims of overt sexual violence.

It was a tough class and highlighted some of the ways I feel like I haven’t been able to make this course in general the kind of class it should be.

It wasn’t tough in the sense that it led to hard, painful conversations. Quite the opposite, actually. The one topic that the guys really seemed interested in there was talking about the details of the war (that’s not unusual – my plan over the summer is to note this clear line of interest and teach a class on the Congo wars). For the rest of the time, it was hard to get anyone to talk.

I suspect – though I don’t know – that part of the problem is that this might be a bit too close to home, while at the same time not being close enough to home, for our students. On the one hand, a constant weird dynamic in the class is that I am a student of violence but my life has been largely untouched by it – this is, of course, not the case for a lot of the guys in the class. On the other, Josh and I made a conscious choice not to have a reading that was directly focused on something like prison rape, for fear that it would be too direct an approach for some of the men (we have at least one student we know to be in prison for rape, so that’s pretty direct, but prison rape is a present threat for at least some of them) – despite the fact that it’s a serious problem, with recent statistics indicating that the number of sexual assaults in prisons (mostly of men) is about even with the number of assaults in the entire nation outside of prisons (both are estimated to be on the order of 200,000 per year).

But, mostly, it was me trying to fill time by talking, and a bit of that professorial, “so, do you see Griffin’s argument? Does it make sense to you?” getting vague assent.

In addition, I worry that I have not used this class as a strong enough platform for engaging on the moral issues that are directly relevant. For example, two sessions ago when we talked about the way that militaries maintain themselves, one of the readings was about the idea that masculinity is a social construction intended to make militaries possible. One of our students basically pushed the – horrible – line that women can’t be allowed into the military because then it’s inevitable that men will rape them. Josh and I both tried to bring the student to understand that that was a pretty backwards way of looking at the problem, but given that more students seemed to be nodding along with him than with us, I fear we failed entirely.

I don’t want to remove blame from my teaching style (or from guys not doing all the readings, and so clamming up – perhaps a side effect of making the reading load a bit too heavy for this class). But our hesitancy to go directly after the issue of prison rape may also have been part of the problem. The most fruitful conversation I had was after class had officially ended, with two of the guys in the class who have been in prison longer-term (though, they are also guys with whom I have a longer and deeper relationship than many of their classmates, so that may be part of the equation).

In a nutshell, they told me two things. First, they said that the kind of rape that happens at least in their prison, has changed over the past decade or so. As they described it, it used to be that it was pretty common for sexual predators to straight-up roam the halls and just grab people who might be out of sight of the guards (as a side note, they focused entirely on rape of incarcerated men by other incarcerated men, though the stats I cited above indicate that a huge amount of abuse is by correctional officers). Now, they said, predators had to operate by “trickery,” and described a more common practice as a guy known to be a predator befriending a new guy and convincing him to transfer to share a cell.

Second, when I asked, “so what do you think changed?” their answer was that it was the beneficial effect of the programs that now exist in JCI, like the Alternatives to Violence Project, and the volunteer college courses that we teach. I can’t verify that! But, walking out of a class where I was feeling a bit of a failure as a teacher, it was a nice thought to have.