Author: prisonscholarsprogram_zfjwjl

-

Marshall Project Launched

A crucial resource launched today: The Marshall Project, “a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization covering America’s criminal justice system.” Check it out at www.themarshallproject.org.

-

Prison Abolition, Reform, and End-State Utopias

(Cross-posted from anotherpanacea.com)

Recently I’ve been thinking about a book by Erin McKenna which I read as an undergraduate: The Task of Utopia: A Pragmatist and Feminist Perspective. I read it then because it promised to bridge the divide between my favorite genre, science-fiction, and my interest in philosophy. But the book profoundly changed me, and I’m always surprised that others haven’t read it; it feels like a classic. Using John Dewey’s work, McKenna articulates what she calls a “process model” for utopias, whereby we distinguish disputes about “end-states” from judgments about the “ends-in-view.” And this has always deeply affected my politics and thinking about political philosophy. I tend to think that far too many theoretical and practical divides are reducible to debates about end-states, such that even though progressives, libertarians, and anarchists all share the same criticism of some aspect of the state, they cannot work together. Usually these disputes are bolstered by philosophical and theoretical apparatus. The divide between prison reformers and abolitionists, for instance, is understood by abolitionists through the lens of Foucault’s critique of the 19th Century reformers, whose reforms, though sometimes well-meaning, only intensified incarceration by making it more exacting and effective while empowering the reformers. Meliorists who merely protests injustices or inequities but do not loudly call for the absolute abolition of prisons are falling into a “carceral logic” by which prisons will inevitably be preserved in all their evils.

Where I find McKenna helpful is, first, in her claim that end-state disagreements tend to be associated with masculine utopias, while feminist utopias emphasize ends-in-view (which jives with my readings of the relevant science-fiction utopias, and also of polital theories that have utopian elements), and second, in her Dewyan typology for judging ends-in-view. According to McKenna’s reading of Dewey, there are five criterion (five questions, really) by which we can judge an end-in-view:

Where I find McKenna helpful is, first, in her claim that end-state disagreements tend to be associated with masculine utopias, while feminist utopias emphasize ends-in-view (which jives with my readings of the relevant science-fiction utopias, and also of polital theories that have utopian elements), and second, in her Dewyan typology for judging ends-in-view. According to McKenna’s reading of Dewey, there are five criterion (five questions, really) by which we can judge an end-in-view:- Does it promote education and participation? Will the people participate in decision-making and goal formation?

- Is it realistic? Does it acknowledge our embeddedness in constraining contexts?

- Is it flexible? Can it be modified as new conditions emerge?

- Does it aim to develop capacities and abilities, not just states of affairs?

- Does it open up possibilities or close them off? Does it promote plurality or isolation? Cooperation or competition? Power or paralysis?

Halden Prison in Norway This is where I find abolitionism frustrating: the project of prison abolition seems like an end-state rather than an end-in-view. It deliberately ignores (1) the wishes of victims, citizens, and even many of the incarcerated (all of whom are understood to be duped and epistemically blinded by the ideology of carcerality unless they adopt abolitionism.) It doesn’t start with our current carcerality and work away from it, but rather starts with a rejection of the current context and the constraints it creates (2). It’s inflexible (3) in the sense that it does not allow that some limited carcerality (a la Norway?) might still be reasonable. Though there’s the sense that that is the direction that abolitionism must proceed, it does not currently emphasize the development of the skills and abilities (4) that alternatives to incarceration would require. And though it does aim to foreclose carcerality forever, I do think abolitionists are most concerned to promote plurality, cooperation, and empowerment (5) for some of the most dominated people in our world today, which is why I can’t help feeling the pull of abolition even as the other objections I mention raise red flags.

Meliorism, on the other hand, has all the problems that the abolitionists describe. Reformers work with and within the system to resist it, which requires all sorts of rhetorical and practical compromises. By chipping at the edges and living too comfortably with “constraints” and “realism,” (2) meliorists leave the status quo mostly untouched. We adopt democratic projects and processes (1), but leave the fundamental injustices in place. We develop capacities (4) but usually we can’t create the institutions and conditions (5) where those capacities will be actualized. We are, at base, flexible (3) with evil, and thereby compromised by it, while the righteous know that evil requires inflexibility and even sacrifice.

Angela Davis puts it this way at the start of Are Prisons Obsolete?:

“As important as some reforms may be-the elimination of sexual abuse and medical neglect in women’s prison, for example-frameworks that rely exclusively on reforms help to produce the stultifying idea that nothing lies beyond the prison. Debates about strategies of decarceration, which should be the focal point of our conversations on the prison crisis, tend to be marginalized when reform takes the center stage. The most immediate question today is how to prevent the further expansion of prison populations and how to bring as many imprisoned women and men as possible back into what prisoners call the ‘free world.’”

No reformer wants to “produce the stultifying idea that nothing lies beyond prison,” but much of the rest of Davis’s book is devoted to the claim that reform is inextricable from that consequence. Ultimately, she equates prison reform with the absurdity of “slavery reform.” America’s prisons are historically and in current practice entangled with the Black Codes, the convict-lease system, Jim Crow, sexism, and antiblack racism; therefore, reformers are merely (hopefully unknowingly) fluffing the pillows while white supremacy and patriarchy is maintained:

If the words “prison reform” so easily slip from our lips, it is because “prison” and “reform” have been inextricably linked since the beginning of the use of imprisonment as the main means of punishing those who violate social norms.

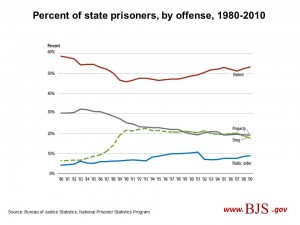

Yet consider: Davis assumes that the majority of the increase in incarceration has been driven by the drug war, and that alternatives to incarceration will foreground drug treatment and decriminalization of drugs. In fact, though the largest group of arrests are tied to drug use, the largest group of prisoners are incarcerated for violence; this reflects sentencing differences and the kinds of treatment diversion programs for which she calls. There’s good evidence that the drug war, poverty, and racist policing produce some of that violence, but not all of it. Plus, prison populations are already shrinking, but at least some of this decline is due to the increase of post-release strategies that export carceral logics into a parolee’s (or even an unindicted suspect’s) everyday life. The goals of decarceration can fall into the logic of carcerality as easily as the goals of reform. So how much really separates reformers from abolitionists? A reformer might call for the restoration of prison education and voting rights, for the creation of schools that teach rather than prepare students for prison, for decriminalization and treatment of drug abuse, for poverty-reduction and racial justice, while still thinking that certain kinds of violence should lead to coercive detention, that restorative justice has dangerous implications when applied to cases of sexual assault or organized violence.

And we see similar strands in Davis:

“In thinking specifically about the abolition of prisons using the approach of abolition democracy, we would propose the creation of using an array of social institutions that would begin to solve the social problems that set people on the track to prison, thereby helping to render the prison obsolete. There is a direct connection with slavery: when slavery was abolished black people were set free, but they lacked access to the material resources that would enable them to fashion new, free lives. Prisons have thrived over the last century precisely because of the absence of those resources and the persistence of some of the deep structures of slavery. They cannot, therefore, be eliminated unless new institutions and resources are made available to those communities that provide, in large part, the human beings that make up the prison population.”

A reformer sees nothing objectionable in those prescriptions, wants to join with the abolitionists for all their ends-in-view and put off the day when end-states might divide us. When the day comes that prisons truly are obsolete, reformers hope that they will be able to see that, too. But who really thinks that today is that day? Not Davis, who wants to “solve social problems” before throwing open the prison doors. In the meantime, why can we not work together to shrink and ameliorate the torturous institutions we all abhor? Why isn’t the reified distinction between abolition and reform as meaningless, today and for the foreseeable future, as the division between those who want to live in a world where the state withers away (Engels) and the world where the state has become small enough to drown in a bathtub (Norquist)? (Norquist now favors some decarceral strategies: is he an ally or an enemy?) If ends-in-view divide us, we must deliberate, compromise, and fight; so long as we are only divided in our utopias, why not collaborate?

-

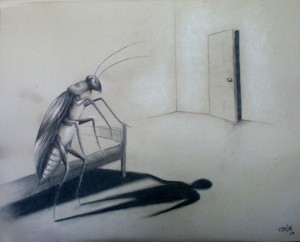

July 23: Final Class on Kafka

There’s always something a little bit sad about the last class of the semester. I’m leaving for a relaxing summer vacation, and the men are… stuck exactly where they always are. In a normal academic environment, the summer is a time for renewal and regeneration – metamorphosis, in fact – but at JCI all seasons are pretty much the same.

There’s always something a little bit sad about the last class of the semester. I’m leaving for a relaxing summer vacation, and the men are… stuck exactly where they always are. In a normal academic environment, the summer is a time for renewal and regeneration – metamorphosis, in fact – but at JCI all seasons are pretty much the same.This week we discussed Part III of the story, and ended up having a long debate about whether or not “insect” Gregor bore any physical resemblance to “human” Gregor. Some of the men imagined “insect” Gregor to have “human” Gregor’s face, which isn’t something described by Kafka. I thought is was probably their own projection on to the story. The men were especially interested in analyzing the story’s “final meaning,” especially the significance of the three bearded lodgers (the “three wise men,” as Mr. Drummond referred to them). We also discussed how, once Gregor is dead, his parents are referred to as “Mr. and Mrs. Samsa” instead of “the Mother and the father. Mr. Luskey suggested this may be due to the fact that they are no longer figures in Gregor’s narrative – in fact, now Gregor is only a figure in the narrative of others – people, indeed, just like us.

-

July 16: Advanced Literature / Kafka

This week, we discussed Part II of Kafka’s “Metamorphosis.” For their homework, I’d asked the men to imagine themselves as Gregor’s sister Grete, and to write a letter to their best friend, giving an account of what’s been happening in their life. Here’s part of Mr. Gross’s response: “Guten Tag Ava. My family is experiencing some troublesome times which explains why I haven’t been able to visit you. Remember how you used to say my brother was creepy? Well, you’re not going to believe this, but now not only is he creepy, he’s also a crawler. He’s turned into a full grown bug. As for me sharing this with you, I should also tell you that only father, mother, the chief clerk and myself know about this, so please keep it a secret because I don’t want our house to turn into an insect zoo.” We’ll be discussing Part III in our final class next week.

This week, we discussed Part II of Kafka’s “Metamorphosis.” For their homework, I’d asked the men to imagine themselves as Gregor’s sister Grete, and to write a letter to their best friend, giving an account of what’s been happening in their life. Here’s part of Mr. Gross’s response: “Guten Tag Ava. My family is experiencing some troublesome times which explains why I haven’t been able to visit you. Remember how you used to say my brother was creepy? Well, you’re not going to believe this, but now not only is he creepy, he’s also a crawler. He’s turned into a full grown bug. As for me sharing this with you, I should also tell you that only father, mother, the chief clerk and myself know about this, so please keep it a secret because I don’t want our house to turn into an insect zoo.” We’ll be discussing Part III in our final class next week. -

Advanced Literature, July 9 2014

This week we started discussing Kafka’s “Metamorphosis” – th

e men had read part I by themselves over the preceding week. So far there’s a general consensus that the story is weird but intriguing. Here’s Mr. Hardy’s response: “Wow! I can only imagine what it would be like to awake and be someone you were not or now seem to be. To be such a creature as an oversized rodent, a Roach. I would much rather be a butterfly or a Praying Mantus even, just not a roach. One who creep late home in the darkest hour to eat An Unwanted creature as this. The rejection from your parents, over something you had no control over. As a child being the oldest I have suffered the blame many times. Yet they always taught, expect the best never look for the worst. No one wanted to just accept the fact that Gregor was sick. For God’s Sake, come on man have a day off. To be hurt by someone who says they love you is always the worse, especially when you are working for their benefit!”

e men had read part I by themselves over the preceding week. So far there’s a general consensus that the story is weird but intriguing. Here’s Mr. Hardy’s response: “Wow! I can only imagine what it would be like to awake and be someone you were not or now seem to be. To be such a creature as an oversized rodent, a Roach. I would much rather be a butterfly or a Praying Mantus even, just not a roach. One who creep late home in the darkest hour to eat An Unwanted creature as this. The rejection from your parents, over something you had no control over. As a child being the oldest I have suffered the blame many times. Yet they always taught, expect the best never look for the worst. No one wanted to just accept the fact that Gregor was sick. For God’s Sake, come on man have a day off. To be hurt by someone who says they love you is always the worse, especially when you are working for their benefit!”More next week….

-

Advanced Literature

Mr. C Doyle on Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Tell Tale Heart”:

Mr. C Doyle on Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Tell Tale Heart”:I liked the story, wish it has been longer. I also liked Poe, and his style of insanity. As soon as I read the line, “I loved the old man,” I knew he was going to die! It was strange how I seemed to be one step ahead of everything that was happening in the story. No matter how careful, cautious, or patient he boasted to be, I knew somehow, someway, he would slip up and wake the old man. The beating of the old man’s heart caused him to lose his cool and throw caution to the side. He leaped into action, killing the old man. It felt weird that I knew (before I read) that the old man’s body would be dismembered.

There is something unusually odd about the way this story was so predictable, like I had already read it before… but I hadn’t. After his death, the manifestation of the beating of the old man’s heart was presented, as he put it, “not within my ears”. So the question is… “If not between his ears, where did the heart beat come from!?” Very mysterious.

-

Advanced Literature summer class 2: Jekyll & Hyde

Our discussion of Jekyll and Hyde turned out to be very thoughtful, even though a couple of the men were absent (ie. in lockup). This is unfortunate, because when things keep changing, when a routine is constantly broken, it can seem unreal, and anyone who experiences it that way is going to feel isolated from the community.

We started by talking about Mr. Hyde. The men were surprised by his appearance. They thought he’d look like a werewolf, or at least have fangs or something like that, but in book he’s a normal men. Stevenson describes Hyde as “much smaller, slighter and younger” than Jekyll, who actually feels “lighter, happier in body” when he’s wearing the shape of Hyde. He may not be physically repulsive, however, but there’s something about him that gives people the creeps. “There is something wrong with his appearance; something displeasing, something downright detestable. I never saw a man I so disliked, and yet I scarce know why”, says one man who meets him. “He gives a strong feeling of deformity, alth

ough I couldn’t specify the point.” To the lawyer Mr. Utterson, “he gave an impression of deformity without any nameable malformation.”

ough I couldn’t specify the point.” To the lawyer Mr. Utterson, “he gave an impression of deformity without any nameable malformation.”

The men also found Jekyll different to how they’d imagined him.“He seems older. Not so innocent,” said Sig. “In the movies he’s always this handsome young guy, but in the book he seems very different.” Stevenson describes Jekyll as “a large, well-made, smooth-faced man of fifty.” Later he describes himself as almost an “elderly man.” “Also, when he’s Hyde, he looks different on the outside, but he’s still Jekyll on the inside,” said Steven. “His thoughts don’t change. It’s always Jekyll’s point of view, even when he’s Hyde.” I asked them to finish the novel by next week, when I’ll be out of town. Our next class will be two weeks from now. -

Congratulations!

Joshua Miller, one of our long-time instructors in the program, has been moving through the application process for the Open Society Institute – Baltimore Community Fellowships program (to support our work at JCI). Yesterday he received word that he has made it through the first round, and is being invited to submit a full proposal. Let’s all wish him luck as things progress!