I’m a little behind on my postings… but here’s an update on the men’s first encounter with Stevenson’s The Strange Tale of Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde. I warned the men that this short novella would be very different from the story we all think we know—that of the upright Victorian gentleman and his evil doppelgänger. Stevenson’s tale is framed as a detective story whose most prominent character in isn’t Jekyll but his lawyer, Mr. Utterson; Jekyll appears only intermittently, and never speaks for himself until the very end of the story. The book is short (it’s less than a hundred pages, and can be read easily in a single sitting), and rather different from movie versions of the story, which turn it into a simple allegory of good and evil.

I’m a little behind on my postings… but here’s an update on the men’s first encounter with Stevenson’s The Strange Tale of Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde. I warned the men that this short novella would be very different from the story we all think we know—that of the upright Victorian gentleman and his evil doppelgänger. Stevenson’s tale is framed as a detective story whose most prominent character in isn’t Jekyll but his lawyer, Mr. Utterson; Jekyll appears only intermittently, and never speaks for himself until the very end of the story. The book is short (it’s less than a hundred pages, and can be read easily in a single sitting), and rather different from movie versions of the story, which turn it into a simple allegory of good and evil.

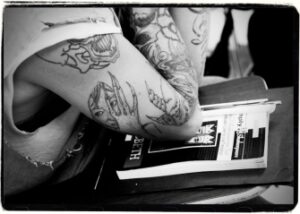

I handed out copies of the book (a no-frills text costing just a dollar), and before starting to read, I asked the men about their impressions of the story from movies they’d seen, from popular culture, or from their own experiences. Most of them knew the basic outline of the tale through The Nutty Professor (the Eddie Murphy version, from 1996), though I was surprised that one man had never heard the names Jekyll and Hyde. The others knew the concept, at least. The men discussed how their personalities had changed when, before prison, they were under the influence of drink or drugs. The conversation then turned to the use of aliases. A number of the men had used different names when they were on the run.

One man told us how he stole a car and fled to California after receiving a 25-year sentence. “I felt free,” he said. “Time went by so fast. Everything was more vivid. Colors were brighter, the sun was hotter, flowers smelled better.” As a disguise, he bought an U.S. army uniform from a thrift store, hoping it would allay suspicion. One night he got pulled over by a police car, and the officer told him he’d just run through a red light. the man rolled down the window and leant his elbow on the frame, flashing his army stripes at the cop.

“I’m real sorry officer, but I’m trying to get back to the base before curfew,” he bluffed. If you write me up for a citation, I’m afraid I’ll be too late.”

To his surprise, the ruse worked. “Alright officer, go ahead,” said the cop.

The inmate was stunned—he hadn’t really expected his disguise to work. “I couldn’t believe it,” he told us. “If the cop had asked anything—where was the base, what time was the curfew was—I wouldn’t have known what to say. But he just let me go. I was driving along laughing, thrilled. I couldn’t wait to tell my buddies. But then I realized, because I was on the run, there was no one I could tell. That was pretty depressing.”